Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

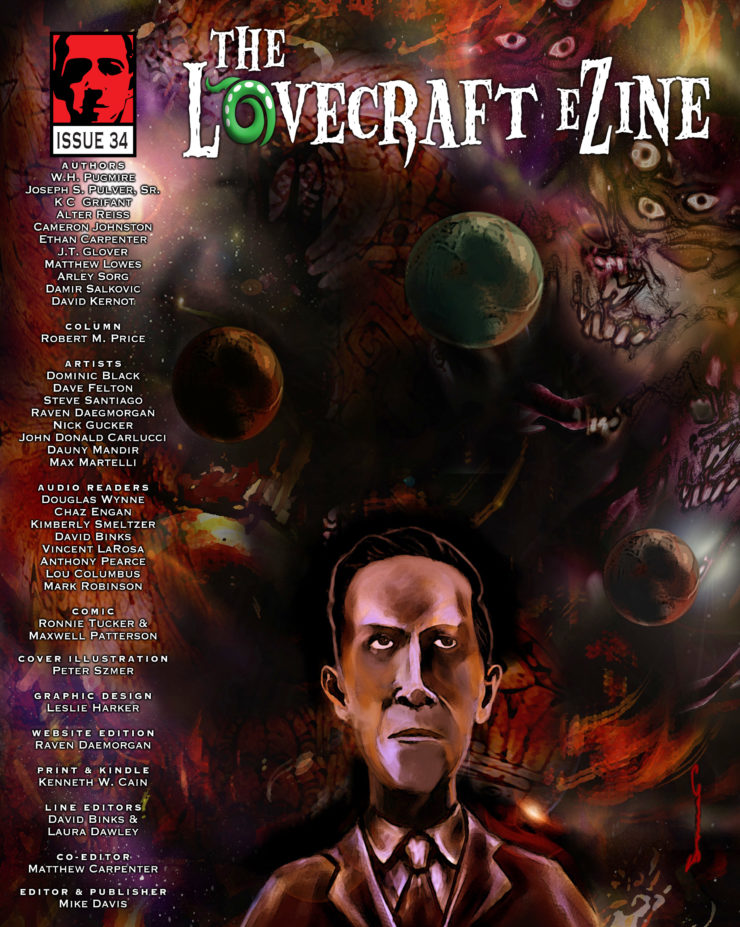

This week, we’re reading Alter Reiss’s “In the Forest of the Night,” first published in the March 2015 issue of the Lovecraft E-Zine. Spoilers ahead; go check out the original, it’s a quick read and has shimmer spiders.

“And who is this,” said the long-necked paneron, from the bole of one of the great, phosphorescent night oaks, “come to our solitary?”

Summary

Abraham Jackson, or as he prefers to be called One-Eyed Jack or simply Jack, walks in the Dawning Wood. A paneron creeps down a phosphorescent night oak to interrogate and taunt him, while the shimmer spiders reel up their threads at his approach. Abraham Jackson isn’t the only one to come into the woods from the mirrored hall tonight, the paneron says. Brightest Star and Black-Cowled Drusus have conspired to trap him for use in a certain ritual. Yes, Abraham Jackson’s own Star, who pretended to be his pupil, but he is too weak and old, and she has—

The paneron, hungry for Jack’s fear, creeps too close. He throws it to the ground, closing his one good eye to its poison, driving the end of his black staff through its throat. As it dies, the paneron gloats on: his enemies will feed his blood to a great one, and prosper from it.

Jack cuts the two gems from the paneron’s heart and sits down. Star and Drusus may have laid on him a spell that directs his every step towards them, but he can hold off on those steps.Beside a night oak he sits more still than death, until the shimmer spiders forget him and lower their strands past the oak roots into the dreaming world. Sparks rise and fall on the strands, the souls of dreamers, each captured by a spider and drawn upward toward the wood. Ultimately the dreamers will wake in the forest of the night, reborn briefly before the spiders’ jaws close.

Jack waits for the nearest strand to be fully extruded. Then he cuts it loose, to the spiders’ rage. He coils up the stolen shimmer silk and walks on. He twists the silk into patterns along with the paneron’s heart-gems, a hank of his own hair, two silver dimes, and nine drops of Kentucky bourbon.

He comes at last upon Brightest Star and Black-Cowled Drusus. Each alone is more powerful than Jack; their magic combined they easily render him helpless. Drusus mocks and kicks Jack, for which Star chastises him: there’s no need to be cruel. To Jack, she apologizes: He was a good teacher, but Drusus’s offer of alliance was too good to pass up, and after all, Jack’s understanding was a bit limited.

The two bring Jack into a magic circle of black iron and nightshade and bind him to an altar stone with silver chains. To keep him conscious and in pain as long as possible, for the great one’s delectation, they cut him and stuff the incisions with burn-weed and wasp venom.

The ritual suspends Jack between life and death in incredible agony for a long time before Star stabs him through the heart. He dies, to wake naked save for a strand of shimmer silk, outside the magic circle.

Buy the Book

Bedfellow

Now it’s Drusus and Star who are trapped inside.Jack stands and studies the sky.There are no clouds, but the encircling trees toss as if in storm winds. You’ve called something up, Jack says. He knows, as do the trapped ones, that they have two choices. Either one of them lies on the altar as sacrifice, so saving the other, or the great one will take them both to be bound to it in torment for all eternity.

Star and Drusus draw their daggers, neither eager to play the noble role. Jack withdraws to the shelter of the trees as the great one comes.It takes what the magic circle offers.Before departing, it gazes at Jack, who bows his head.

He returns to the altar long enough to retrieve his staff and clasp-knife and consider what little’s left of Star and Drusus. The denizens of the mirrored halls will be surprised when Jack returns instead of the ill-fated pair. For a while they’ll fear him. Then, when he fails to perform wonders, they’ll forget. They’ll forget well before it’s time for him to make his next offering—just as he was promised.

What’s Cyclopean: Lovely, evocative creature-names—paneron and shimmer spider, kite and breakshell—invoking a whole ecosystem probably better avoided without heavy protective equipment.

The Degenerate Dutch: No recognizable in-groups from our own world here, though the mirrored halls sound pretty degenerate.

Mythos Making: Jack’s patron is “not one of the more pleasant great ones.” It’s not clear who, or what, would fall into that latter category.

Libronomicon: No books this week.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The closest we come to madness is Drusus’s petty irritation at Jack for taking his time on his way to the altar.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

This week’s story is clearly Lovecraftian, because people are getting sacrificed to Great Old Ones and it’s in the Lovecraft E-Zine, and there’s a bourbon-laced splash of American folklore in there too, but I have to admit that the weird creatures lurking in a weirder wood made me wonder if the wood in question might be kind of… tulgy.

Beware the shoggothim my son

The blobs that bite

Plasms that snatch

Beware the Shantak bird

And shun the squamous Bandersnatch.

I’m kind of surprised that we don’t have more Carroll/Lovecraft hybridization. The moods of the originals are different, but they have in common the underlying irrationality of existence. Can’t you picture Alice spending a lazy day with the cats of Ulthar, or Randolph Carter making his narrow escape from the Queen of Hearts? But then, I’m always interested in the many ways that people deal with the aforementioned irrationality, beyond the worldview-breaking anxiety that was Lovecraft’s obsession.

One-Eyed Jack is neither anxious nor absurdist—he’s taken another path, that of the trickster who’s joined forces with the universe’s irrationality and (in this case) malice. Given the season, I’m put in mind of Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, where the Jacks make up a mutual aid society of such tricksters, a cosmic force in their own right backed by all the stories of Jacks as clever sons and giant-killers… and killers of other things.

One-Eyed Jack is backed by something much simpler, a deal with a familiar sort of devil. Here we get the Problem of Sacrifice—why do the incarnations of an uncaring universe care so much about sapient blood, pain, and/or souls? We’ve encountered some good answers to this question. My favorites focus on the sacrifice’s meaning for the people carrying it out, leaving its meaning for the gods if any opaque—though “art preservation” also works pretty well. The thing is that, much as modern cultures generally have strong taboos against human sacrifice—and mind you, I’m pretty happy with this state of affairs—the cultures that embrace it tend to do so as a tool for order and social binding rather than chaos and unmaking. In literature, by contrast, it more often serves to demonstrate just how unsavory a particular entity’s tastes run.

Or how unsavory a particular Jack might be. This one goes from giant-killer to ripper as nimbly as any of Gaiman’s. He remains interesting to follow, if only because he seems to prey on those who first betray him. Though perhaps the inevitability of that betrayal is part of his Deal, in which case we get autonomous-car-level ethical questions about culpability.

Which are made more interesting by the title. What’s found in the Forests of the Night is a Tyger, Tyger, its fearful symmetry shaped by an immortal hand or eye. And tigers (or tygers) are predatorily innocent. So is Jack the Tyger, shaped as living bait? Or is it the Old One, nature shaped by blind evolutionary forces alongside the formation of the stars?

Or is it the whole tulgy wood, full of panerons and shimmer spiders, all looking for their next meal, whatever form of sustenance has been decreed for them? Possibly this is a story about predation rather than sacrifice—about great old ones and spiders and jacks all filling their necessary ecological niches, nature red in tooth and claw and shimmer-silk strand.

Anne’s Commentary

Is it still a thing in grade school, in high school even, to memorize poetry? It was definitely a thing in my Precambrian day, when all we good little soft-bodied Ediacarans would recite together, “Tyger, tyger, burning BRIGHT/In the forests of the NIGHT,/What immortal hand or EYE/Could frame thy fearful symmeTRY?” All the while wondering why William Blake couldn’t spell or rhyme (tyger? eye-symmetry?); also, what even was this vertebrate mammalian predator of which Mr. Blake spoke, and why was it on fire?

In Alter Reiss’s forest of the night, there is no tiger, ignited or otherwise. No, nothing so homey as that, for we are once again snared in nightmare. That, or we’ve passed into what Hagiwara called “the reverse side of the landscape,” the place that lies beyond the dream we call reality. Either way, Reiss’s story creates a narrative space with the imaginative grip of Lord Dunsany’s fantastic creations and Lovecraft’s Dreamlands; and as with these spaces, its hallmark is evocative economy. What do we know about panerons? They have long necks, and claws, and can scuttle on tree trunks and leap from one to another agile as squirrels, and spit venom, and speak in human tongues, and feast on harsh emotions, and provoke them with harsh truths they’ve harvested with what, quick ears for gossip, telepathy? Bits of information, doled out as the opening progresses, as snatches of observation from viewpoint character Jack who, as it turns out, is not really ignoring the paneron, who’s watching for his chance to… slaughter it for its two heart-gems. Heart-gems!

My imagination’s going double time filling in gaps on this creature, which is as it should be. I’m seeing something between a gecko and a spitting cobra, with a great interest in the politics of both Forest and Mirrored Hall. Then there are the shimmer spiders and the crucial question they open about which world is “real,” the Forest or the nether-root realm the spiders fish for the souls of dreamers.

“Who is this come to our solitary?” is the paneron-posed query that opens “In the Forest,” rather like “Who goes there?” opens Hamlet. Except First Paneron knows very well who it is, or thinks it knows, and is merely warming up for its taunting assault. When at story’s close the far less cocky Second Paneron asks, “Who are you, Abraham Jackson?”, its question is sincere:Who and what is this guy, really? He’s not what he seems, a failing old man and weak magician, or he wouldn’t be the one returning to the mirrored halls. Even more to the point, he’s not what he wants to seem. But as if some law of magic compels him to answer this one question truthfully, our pretender tells Second Paneron “I’m Jack.One-eyed Jack, if you prefer.”

He also tells First Paneron he’s One-eyed Jack, when it’s dying and the knowledge can do it no good. What’s the significance of the moniker? First thing I thought was it had a frontier America sound to it. His clasp knife added to the impression. Throw in among his magical paraphernalia two silver dimes and drops of Kentucky bourbon, and this fellow has definitely dropped into the Forest of the Night from some high ridge of our own Appalachian mountains.And why not, if Randolph Carter could access the Dreamlands from the lesser summit of College Hill? Or if Jack didn’t go willingly into that Forest, perhaps he was one of the dreamers drawn up and up a shimmer spider strand until he passed from the unreal bubble of our world into the too-real existence that included hungry spinner jaws.

Only Jack didn’t succumb to those jaws. Jack went from dimension to dimension with his cunning intact, and he escaped from his spider-captor, and he went on to prosper in his new reality, and why not? He just happened to be suited to the place, being a one-eyed Jack, like he of Spades and he of Hearts, who show only one side of their faces.In the mirrored halls, everyone looks at reflections, which reverse reality. The Brightest Star is the darkest traitor, to be matched only by her own “ally” Drusus. One’s worth is judged by the enemies one makes.Safety lies not in showing strength but in feigning weakness. Fool everyone, us readers included, into feeling sorry for the poor old man going to his doom, until bit by bit we realize who was in charge all along, who the great one’s favored servant actually is and will be again.

Beware the One-eyed Jack, see, because he shows you the good side of his face and hides the bad. Where Abraham Jackson’s concerned, “good side” equals the side it profits him to show you. Until it doesn’t anymore. Then he can reveal the “bad side” of wizard powerful enough to return from the dead, oh did you miss my little shimmer silk and bourbon talisman there?

Good old Jack. Or bad old Jack. Depending on whether it’s all a dream or only too real, yet another debate for the still-expanding regulars table at the Cat Town-Ulthar Teahouse-Inn. Meet you there!

Next week, a follow-up to the ill-fated and infamous Dyer expedition in John Shirley’s “The Witness in Darkness.” You can find it in The Madness of Cthulhu.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.